The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the stark contrast between cities with and without cars. It’s now time to talk honestly about the stark contrast between mobility services that add them to cities, and those that don’t.

The average gas-powered vehicle uses 104 ft² of public right-of-way per rider and emits anywhere from 375 to well over 450 grams of CO2 per passenger mile. If the car happens to be part of a ride hailing platform like Uber or Lyft, its carbon emissions jump to as high as 700 grams/mile.

A shared electric scooter, by comparison, uses around 12 ft² of public right-of-way per rider. If it’s a Bird Two, it also only emits 97 g CO2e/pmt—a number that continues to drop every year. This equates to a significant decrease in both public space occupied and air pollution discharged.

Despite the comparative benefits, however, electric scooters often face an uphill regulatory battle in many places for one key reason: cities have historically been built around automobiles. As law professor Greg Shill recently wrote in an article on the shifting mobility paradigm: “Cities were quite literally bulldozed [in the 20th century] to make room for cars. The resulting transformation left little space for any other mode of personal transportation.”

The problem isn’t limited to just scooters. In a survey of the top ten most bike-friendly cities in the US, cyclists made up less than 3.4% of commuters (for comparison, more than 25% of all trips in the Netherlands are made on two wheels).

The regulatory bias towards cars is perhaps most clearly on display when looking at ride hailing apps. According to their recent report on the climate risks of ride-hailing, the Union of Concerned Scientists states that: “Most cities limit the number of taxis…In contrast, ride-hailing regulations are very much a work in progress, even as numbers of ride-hailing trips vastly surpass taxi trips in US cities.” This despite the fact that a “typical ride-hailing trip is about 69% more polluting than the trips it replaces, and can increase congestion during peak periods.”

So that’s the bad news. The good news is that there are three very specific things that cities can begin doing today to help transform urban mobility away from cars and towards more sustainable, less congested forms of transportation:

- Redistribute Mobility Fees

- Set Dynamic Fleet Caps

- Minimize Geofencing and Speed Zones

1.) Merit-Based Mobility Fees

Charging privately-owned micromobility companies an operating fee can be a good thing, especially if it leads to things like the construction of new bike and scooter infrastructure. These fees, however, should be reasonable, applied across the entire mobility spectrum and weighted in favor of sustainable alternatives that take up less space on the road. This is unfortunately not the case in most cities.

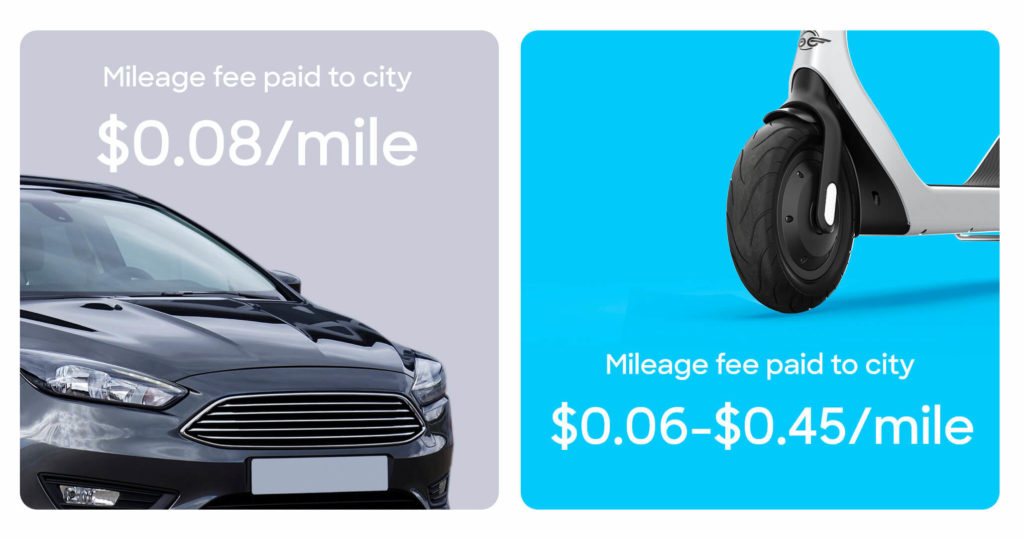

Currently, ride hailing companies in the US are charged an average of $0.50/trip, equalling around $0.08/mile. Scooter companies, by comparison, are charged anywhere from $0.05 – $0.36/trip, equaling between $0.06 – $0.45/mile. Some cities add an additional yearly fee of between $100 to $300 per scooter, creating large upfront costs that surprisingly do not apply to ride hailing vehicles.

As Greg Shill points out in his article: “California taxes scooters at roughly 30x the rate it taxes Uber and Lyft rides. If California…were deliberately trying to disadvantage green, affordable new mobility products versus their carbon-dependent, costly alternatives, it could hardly do so more effectively.”

2.) Dynamic, Data-Backed Fleet Caps

According to the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), approximately 125 micromobility vehicles are necessary per square mile in order to achieve modeshift:

“Research on transit users finds that most people will walk no more than ½ mile to get to commuter rail, with a large drop-off beyond ¼ mile. The distance someone will walk to use a bike appears to be much smaller—about 1,000 ft or 5 minutes walking.”

Interestingly, this issue is already top of mind for many of our riders. In a recent Bird survey conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 1 in 5 respondents identified the lack of nearby vehicles as a concern when quarantine measures are eventually lifted.

To keep trip fulfillment rates high, Uber and Lyft engage in something called deadheading—the congestion and emission-heavy practice of driving without a passenger in order to find fares. Shared scooter and bike services operate differently, relying on appropriate fleet sizes to achieve fulfillment goals. But how can you accurately and intelligently gauge how many vehicles are enough?

One simple but highly-effective way of doing this is by creating a dynamic cap, or a system in which operators who consistently record more than a given number of rides per vehicle per day are allowed to incrementally increase their fleet sizes.

3.) Minimal Geofencing and Speed Zones

Cars and ride hailing services have no geographic requirements and few, if any, restrictions on where and when they can operate. Electric scooters, by contrast, are often subject to a variety of service limitations including curfews, geofencing (i.e. areas where riding and parking are prohibited) and speed zones (i.e. areas where speeds are electronically reduced to as low as 3 mph).

Are such restrictions necessary? That depends. As a tool to be used sparingly in order to help guide rider behavior, yes, they can be beneficial. The problem is that they’re highly prohibitive when overused. In one recent example, bi-weekly ridership in a major Californian city plummeted 50% from 440,000 to 220,000 in the three months following the enactment of such measures.

The reason for this is twofold: riders often report feeling less safe on scooters traveling at very low speeds, and modeshift almost always suffers in heavily geofenced areas. The freer people are to use micromobility, the more likely they are to consistently rely on it as a primary source of transportation.

Takeaways

Ongoing global quarantine measures continue to show us the very real benefits of cities with fewer cars. It’s now time to ensure these learnings translate into action.

The three policy changes outlined here, along with an increase in protected infrastructure, will help cities move away from costly and environmentally damaging car hailing services and towards more efficient and sustainable alternatives.

- Redistribute Mobility Fees to favor safe, sustainable transportation options through funding protected bike infrastructure

- Set Dynamic Fleet Caps to enable service providers to meet demand

- Minimize Geofencing and Speed Zones to ensure that modeshift becomes a permanent practice